and updated by Charles Dewey, 2019

for the Bennington Centre Cemetery Association

Estimated read time: 25-30 minutes

The burying-ground in Old Bennington, formerly known as Bennington Centre, is the oldest cemetery in Vermont. Its importance was well stated by the Legislature in 1935 when the Old First Church and the Bennington Centre Cemetery were declared Vermont's "Colonial Shrine":

The burial ground is the first and oldest cemetery in the state, where lie the remains of five governors of Vermont, seventy-five Revolutionary soldiers, the author of Vermont's Declaration of Independence, the founder of the Vermont Gazette, the patriots who fell at the Battle of Bennington, the Hessian soldiers who died of their wounds in the first meeting house converted into a temporary hospital, together with scores of others who labored for the stability and prosperity of Vermont.

Origins

The history of the old burying-ground really starts in 1762, the second year of the settlers' arrival. The first year they had been preoccupied with clearing fields and building cabins, too busy to decide where their burying-ground would eventually be located. It was assumed that it would be located next to the church, wherever that might be built. In February 1762 a decision was made to locate the proposed meetinghouse near the northeast corner of Land Right 27, which today would be near the Fairdale Farms property, west of Gypsy Lane near Walloomsac Road. Had that plan been carried out, the cemetery would have been located about a mile west of its familiar location.

The change of plans apparently came sometime in the summer or fall of 1762 (there is no record). The new site was the main road junction approximately in the center of the township. It was on land of the leader of the settlers, Captain Samuel Robinson, who was probably pleased to make the site available. The site seems to have been chosen by a committee of the Proprietors, i.e., the owners of land rights, who probably drove a stake in the ground there, as was the custom. That fall, before any construction work on the meetinghouse seems to have begun, the first burial took place when the widow Bridget Harwood died while working in the fields at the age of 49. Her gravestone is near the back corner of the present church, some distance east of where the stake marking the proposed site of the first meetinghouse must have been driven. The grave is marked today by an old stone, but because there were no gravestone makers in the community at that time, one can suppose that the grave was marked by a wooden stake, as was the custom at the time.

First Bennington Deaths

Most local histories accord the widow Bridget Harwood the dual distinction of being the first female settler to reach Bennington as well as the first settler to die here. But to clarify the record it might be noted that another woman seems to have settled here a few months before Bridget, and another settler seems to have died here more than a year earlier. This first female settler seems to have been Hanna Robinson, who came with her husband, Samuel Robinson Jr., in advance of the other settlers, on March 25, 1761, when she was 19 years old and her husband was 23. With them was a daughter, Mary, born before they left Hardwick. The infant did not survive the first summer, dying August 28, 1761. The Harwood claims were certainly unintentional exaggerations based on the story of Bridget Harwood's dash on her horse to be first among the first group of settlers to arrive in Bennington, and the dramatic circumstance of being the first adult settler to die here and be buried in the cemetery — allegedly borne by the same horse on which she won the race across the town line. The Robinsons knew the facts, it is said, and saw no point in protesting minor details.

In any case, little Mary Robinson could not be buried in a churchyard that had not even been designated at the time. She was probably buried on her parents' land, which would be in the Silk Road area. The mother, Hannah, died five years later at age 24, and she is buried in the Bennington Centre Cemetery. As the boundaries among the land rights were not yet clear, the cemetery might have been considered to be in the northeast corner of Land Right 28 or the northwest corner of 29. Twenty-eight was the land reserved in the original land grant from New Hampshire to reward the first settled minister, duly claimed by Jedidiah Dewey. But the spot chosen for the buying-ground was agreed to be in Land Right 29, owned by the leader of the settlers, Samuel Robinson Sr. On May 15, 1766, the Proprietors voted to trade six acres elsewhere for three acres "where the meeting-house now stands," and on August 20, 1766, they resolved that their legal committee ("the prudentials of the propriety") should be sure to obtain title documents and that "Esquire Robinson should be secured for the same."

Church/State (In)distinctions

It should be noted that church and state were identical in early Bennington. The Proprietors were leaders of both church and government. This was possible only because Samuel Robinson Sr. had been successful in making his community a one-church town. It was much later, when the doctrine of church-state separation made some slight impression on the community after Vermont adopted the U.S. Constitution, and when the old system of Proprietors was replaced by Selectmen who had no part in church affairs, that the town of Bennington and the Congregational Church quietly and gradually went their separate ways. So when the "new" meetinghouse was built in 1805-6 the congregation had to raise the money, but the land around the church had devolved upon the Selectmen. Even in modern times, the Selectmen of the town have been in control of the cemetery and the land on which the church stands.

While the public land in 1766 comprised three acres, the older part of the cemetery measures less than one acre. When a school was organized in 1780, it was given a place on the public lands east of the meetinghouse. An animal pound was also built there. The boundaries of those original three acres are not known at this time, so they may or may not be entirely within the present cemetery.

It is not until 1777 that the earliest direct reference to the cemetery is found in the records of Bennington. At that time, the Proprietors appointed a committee "to regulate the burial ground by drawing lines in a proper range so that the ground may prudently be used & to let out the burying yard on conditions such as being fenced & …" (here the passage stops abruptly, as if the clerk ran out of ink or was called away). If the committee made a map, its existence is unknown.

Allowing cattle to graze in the cemetery was the early method of mowing, as shown by a resolution in 1782 to accept the offer of Timothy Follett to fence in the burying yard "with a good decent board fence and make a good gate for an entrance into the same, for the benefit of pasturing the same with such creatures as shall not damage the graves, the creatures permitted are horses, sheep, cattle, for the term of ten years provided he keeps sd. fence in good repair."

The Battle of Bennington

The Battle of Bennington on August 16, 1777, produced a mass grave in the cemetery, marked by a stone in 1896, under which lie the remains of an estimated fifty soldiers from both sides, who died of their wounds enroute to town from the battlefield or in the field hospital located north of the present cemetery, behind the Catamount Tavern. Those who succumbed were buried over a period of days and weeks after the battle. An oral tradition of descendants of German mercenaries who settled in the Mohawk Valley has placed the number of German wounded who died here at thirty-three. One can estimate that our forces would have suffered about ten deaths from wounds after the battle. The American dead would be mostly men of New Hampshire, and some from Massachusetts and Vermont. The enemy dead were mostly Germans from the province of Brunswick, certainly some American Loyalists, probably some English soldiers and Canadian militiamen, but not necessarily any true Hessians, from the province of Hesse, of whom there were only a few artillerymen involved in the battle.

The only soldiers killed at the battlefield whose bodies were carried back to town were two local men, John Fay and Henry Walbridge. A third man, Nathan Slark Jr., was brought back wounded and died some months later. These three are all buried in marked graves. The fourth local man, Daniel Warner. seems to have been buried at the battlefield. The death of John Fay had a tragic aftermath. His son, aged four years, died exactly a week after his father, and his widow, Mary Fisk Fay, died exactly two weeks after her husband, at age 39. Four weeks after John Fay's death in the battle, a son of five years died.

In the year after the battle, the first gravestone carver migrated here from Connecticut, attracted by the white marble available from a quarry in West Shaftsbury. He was Zerubbabel Collins who cut thirty-eight of the stones. Another was Josiah Manning, who carved the stone of the Rev. Jedidiah Dewey. These stones were often carved in the shop during the winter, the inscriptions being filled in on the spot at the wagon of the craftsman in his summer journeys.

Clio Hall

In 1780, the Academy called Clio Hall was built east of the meetinghouse. It was a small wooden structure, located where the present-day church stands. The foundations still exist in the basement of the church. Clio hall was never a successful academy, suffering from lack of endowment and qualified instructors. In 1792 it closed for the last time, when Samuel Dwight was headmaster. Dwight gave up teaching and became a gravestone-cutter, producing one of the stones in the cemetery.

Then in 1803, Clio Hall burned down at a time when the congregation of the church, after long indecision, decided to build a new meetinghouse. Due to the theoretical separation of church and state, and the building of a courthouse near the top of the "up-hill" (where the monument is today) in the 1780s, the new edifice was planned to be solely a church, and to look like one. The new meetinghouse was almost double the size of the old one, and built in the best architectural style. The funding, coming from the pockets of a congregation that was used to having the expense of church-building raised by taxes on land, created the opposition that had taken so many years to overcome. A great revival in 1803 and the absence of a minister helped the proponents of the new church prevail. Eventually a site committee drove its stake in the ground near the old meetinghouse, but the destruction of the old Clio Hall building gave the committee the idea of moving the site eastward to the Clio Hall ruins to allow space for an enlarged "Parade" (green) in front of the new church building.

Grave and Stone Relocation

There was a problem. Burials had taken place around the old Clio Hall, so that the foundations for the new church as planned would have to be built over and around existing graves. The committee argued that in the mother country, graves were often located under churches. As the proponents of the site carried the day, some of the dissenters moved their dead, but most of those graves were not moved, so they remain under the present church. The stones were all taken out. The younger Rev. Isaac Jennings says in his book The Old Meeting House that in his boyhood, perhaps around the Civil War, he saw those gravestones leaning up against the foundation or lying on the ground beside it, where they had been since about 1805.

This raises the interesting question as to whether there are any actual graves by the northwest corner of the church where so many tourists admire the quaint old stones. It seems possible that there are no graves there, and that the first two or three ranks of gravestones so nearly lined up are the stones of those actually buried under the church. One clue which seems to support this theory can be found in the 1835 map of Bennington by Joseph N. Hinsdill, which shows the outline of the church building with a boundary line around an adjacent area, presumably denoting the extent of the burying-ground that year. This line does not take in the land near the northwest corner of the church building, which may suggest that the area was vacant and available when someone undertook after 1835 to set up the stones that Jennings remembers lying around the foundation.

Why set the stones up in that location, and why should the fact go unrecorded? The answer may lie in the tourists who began to summer in the area after the railroad reached here in 1852. Tourists caused the growth of the Walloomsac House across the street, not to mention hotels in the larger village down the hill. If it became logical to clean up the appearance of the gravestones lying around the church foundations, and if they were too historic to be thrown away, why not set them up for the visitors to look at? And if that were done, why publicize the fact?

Perhaps the person most directly responsible was William S. Montague, who wanted to improve the appearance of the cemetery at the end of the Civil War. In any case, it is not known whether Montague was connected with the tourist business at that time, or whether he was one of the many who felt that the appearance of the cemetery was disgraceful and that the Selectmen were refusing to do their duty. The church congregation had refurbished the church in 1865, and had naturally left the cemetery alone. Montague seems to have approached the Selectmen with the idea that he would personally put up money for improving the cemetery if they would make certain expenditures on it. That was agreed, and the effort included work on the headstones, which were set "upright and regular." Was this the time at which the uprooted headstones were planted where perhaps there were no graves? One would think so, evident in photographs supposedly taken around that time. But all this is rather speculative; perhaps more facts will be uncovered.

Montague also began work on a receiving vault, but stopped after the foundation was laid. In the roof of the vault, when it was finished about 1883, were placed footstones and headstones "which had been taken from the old part of the yard several years previously in fixing up the same." It might be noted that while we see only headstones today in the old part of the cemetery, the graves at one time had footstones, shaped-like headstones but smaller. These stones were designed in early times to suggest the headboard and footboard of a bed, in which the deceased slept. A footstone for Rev. Jedidiah Dewey has been located at the residence of his local descendants, who previously considered it a rejected headstone.

Demographic Changes & Cemetery Expansions

In the year 1829 the Selectmen for the first time (so far as it is known) purchased land to expand the burying-ground. For $175, they obtained from Franklin Blackmer, proprietor of a store located on the corner southerly of the church, an apple orchard of about one-third acre located on the easterly side of the burying-ground. The apple trees were left growing, and sixty years later a fel-Tr a-them were still there among the graves. Blackmer did not sell all the land he owned on that side of Church Street, and it was probably on the land he retained that he or his descendants built the carriage barn that protrudes into the cemetery.

The War with Mexico in 1836-7 produced one of Bennington's more notable military burials. Col. Martin Scott was born on his parents' farm on Walloomsac Road and made a career of the army service. After surviving several conflicts in Mexico, he was killed at the battle of Molino del Rey. His body was brought back in an iron coffin for burial here. Another burial in those years was Mrs. Harriet Conkling who drowned in the Hudson River wreck of the steamer Swallow, one of the river boats Bennington residents used in the 1840s for travelling to New York City. The cemetery is also the resting place of Charles C. Jones, who was drowned when the Titanic sank in 1912. His was one of the few whose bodies were picked up by rescue boats.

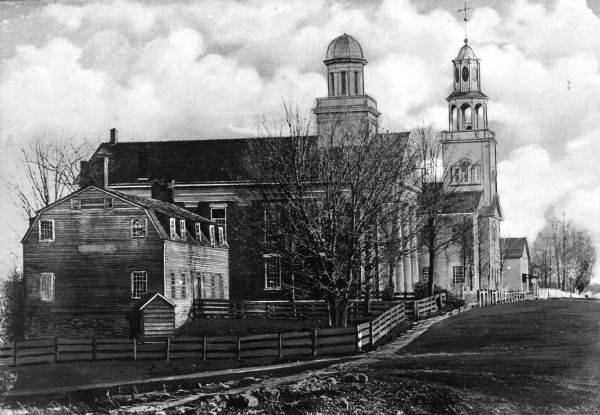

Due to the rapid growth of population in the lower village, which surpassed the hill community about that time, the road down Town Hill was opened in 1841. "East Bennington" and Old Bennington were involved in a bitter rivalry over the location of the post office, since in those days one walked to the post office to pick up the mail. In the fall of 1846 the courthouse (the second one, still on the hill near where the Monument is today) burned, and the efforts of the residents of the lower village to have it rebuilt down-the-hill increased the bad feelings. The legislature gave the honor to the hill dwellers,so the new building was built in what today is part of the cemetery, just north of the Old First Church. The land was purchased from the Squier family by the County of Bennington. By that time, Truman Squier had passed away, and the old farmhouse had become a tin shop, as can be seen in a classic photograph of the time. The present county courthouse on South Street is a copy of the previous one in the cemetery.

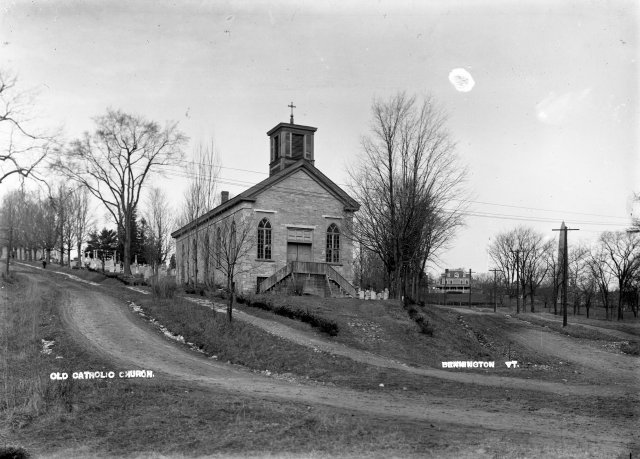

The year 1861 brought not only the Civil War, in which Vermont involved itself so gallantly, but also the first private expansion of the cemetery. This was carried out by Aaron L. Hubbell, presumably for profit. Hubbell had bought the land a few years earlier from the Squier heirs, It was a wedged-shaped half-acre, located along the road down Town Hill near to, but not touching, the Catholic property. He laid the land out in 46 lots, with alleys between lots four to six feet wide and a fifteen-foot road into the cemetery on the northerly side opposite Catamount Lane. Until about 1960, this roadway was in use but the traffic congestion of a funeral procession of automobiles outside the cemetery prompted the association to build steps, which stopped vehicular traffic.

When a purchaser for a lot was found, Hubbell conveyed the lot to the Town of Bennington for a price. The Town then resold the lot to the purchaser at a higher price. For example, in 1864 when former Governor Hiland Hall was willing to pay seventy-seven dollars for a triple lot, Hubbell sold the lot to the Town for fifty-five dollars and the Town conveyed it to Hall for seventy-seven dollars. It isn't clear whether this was done out of fear that only the Town could give a valid deed to a cemetery lot, or whether the Town was exacting from the parties a sort of tax to defray the expenses of taking care of the cemetery.

Two local Civil War dead were brought back from Southern battlefields for burial. One was Captain Frank Ray, killed at Mt. Laurel, Virginia, in 1864. The other was Colonel Newton Stone, killed in 1864 at the Battle of the Wilderness, where Vermont suffered a thousand casualties in a few hours, some by burning to death in brush fires. Colonel Stone was from Readsboro. He was twenty-seven at the time of his death, and was engaged to be married. For years after his burial here, his fiancee came regularly to decorate his grave. The plot for Colonel Stone's burial in 1866 was purchased from the Selectmen by Marshall Carter Hall, oldest son of Hiland Hall.

In 1869, the "fire-proof" courthouse in the cemetery burned down. There was no longer any chance to rebuild it anywhere on the hill, for by now East Bennington had already obtained the post office and with it, the very name of Bennington, forcing the hill community to change its name to Bennington Centre to avoid being called West Bennington. The new Bennington easily won the courthouse, and the fourth one was built on South Street. The former site surrounded by the cemetery was sold by the County, not to the Town, but to Charles R. Sanford, an undertaker and businessman of Bennington Centre, who re-sold it immediately to his brother, Samuel B. Sanford. Samuel was a local man who had moved to Troy and would become wealthy in the shirt manufacturing business. The venture into cemetery development may have been an investment opportunity pointed out to him by his brother the undertaker. Samuel left the old courthouse site vacant, but in 1871 laid out a small parcel located north of the-Hubbell development, into sixteen lots with alleyways between, and began to issue deeds to purchasers. He did not pass title through the Selectmen as his predecessor-developer, Aaron Hubbell, had done.

|

| Conceptual map of the original burying-ground and the lands added over the years. |

In 1875, the Selectmen decided to lay out the "new burying-ground." They had been selling lots in it since about 1866 but had never filed any formal plan. The one they filed in 1875 called for 130 lots with the usual alleyways. This put the Town in the cemetery development business the same as A. L. Hubbell and Samuel B. Sanford, with the possible difference that the Selectmen may have been looking for a source of income to offset expenditures involved in maintaining the cemetery, rather than a profit. In any case, the purchasers in the 1870s and 1880s were not very careful to record their deeds, and because the Town didn't make any apparent effort to keep track of burials, there is uncertainty about who is buried in some of the earlier plots of the "new burying-ground."

The next expansion of the cemetery was carried out by local undertaker Charles R. Sanford in the 1880s. This parcel was farther up the hill than the previous parts, being close behind the old Squier house. It was large enough for 75 lots with the usual alleys.

Decades of Neglect

The appearance of the cemetery was being noticed and complained about by more and more people. As time went by, some who were convinced that it was the duty of the Selectmen to spend public money to keep the appearance of the cemetery up to their expectations were becoming increasingly incensed. This problem was not anything new, of course; the cemetery had looked terrible for decades. The following complaint appeared in the local newspaper in 1831:

It is represented that the field of graves in the Centre Village is made a cow yard and horse pasture. Would it not be well for our town authorities to inquire into it, and let the public know by what right individuals do this? It is not only an outrage upon public feeling which heathen people would commit, but it is injurious to the mounds over the recently buried, and to the just positions of the tomb-stones which mark the burial place of relatives and friends. Affection would often times place the rose bush or the flowering plants to ornament the last receptacle and beloved objects, was it not for this depasturing the ground set apart as sacred to the remains of the dead. A remedy should be applied to this heathenly and unfeeling practice.

Fifty years later the complaints were louder and more frequent. For example, in the 1880s, the editor of one of the newspapers (who may, after all, have been supporting the Selectmen) threatened to publish the names of the families who neglected to take care of their lots.

People living on the hill, and those who had migrated throughout the country, leaving relatives buried in the cemetery, charged the Selectmen with spending too much money on the various cemeteries of the Town, such as Hinsdillville and Chapel Road and above all, the East Main Street location, while slighting the historic cemetery on the hill. The feeling on both sides was exaggerated from the animosities of the previous two decades. In the middle was the Arbor Club, which somehow had become responsible for keeping up the appearance of the cemetery without funds, a gallant attempt was not working.

Seeking Solutions

In 1887, a hundred concerned citizens led by S. N. Sibley decided to petition the Legislature for a corporate charter authorizing them to take charg e of the cemetery. They got their charter easily and found at their first meeting they did not own the cemetery as they expected, but were only authorized to own it. As the cemetery belonged to the Town, except for the lots that belonged to purchasers or their heirs, it is difficult to see how the Legislature could be expected to turn over to the association that which the State did not own. Regardless, the newspaper called the affair a "blunder" and insisted on an amendment. The amendment was never obtained, and the organization died. The cemetery remained unkempt. Photographs of the so-called Hessian Monument show knee-high grass with wildflowers in the background.

But help was on the way. For one thing, the Legislature was taking an active interest in cemetery care and in 1895, it required all towns to receive and invest moneys donated by individuals for the care of burial lots. This was an early form of perpetual care, administered through the treasuries of the Towns rather than through a cemetery association, as is the modern practice. Some owners of lots in the cemetery made such deposits, and the present-day association's treasury still receives payments periodically. As the Bennington Centre Cemetery perpetual care program became available after 1907, however, the deposits were made with decreasing frequency until the last one, at least for the cemetery, was made in 1947. Other cemeteries in Bennington, which do not have their own perpetual care programs, are still encouraging deposits to the Town treasury.

The other development that helped the Bennington Centre Cemetery clean up its disgraceful appearance of those bad years was the renascence of the hill community, which extended from the completion of the Monument in 1891 until around World War I. This blighted area was transformed into a summer colony of more-or-less elegant homes and estates by wealthy outsiders, mostly from Troy and New York City. Some were retired here, although not many, and some were local people who had made their fortune elsewhere and returned each summer. They were remarkably energetic. They moved houses, built mansions, tore down old structures, put in a water system, organized a village government under a charter from the Legislature, formed a country club in a defunct school and set up a library in the Old Academy. Then they got busy fixing up the old cemetery, whether they meant to be buried there or not.

One who did mean to be buried there was Governor John G. McCullough. He had been successful elsewhere in his own right, was the elected governor of Vermont in 1902-4, and was a member by marriage of the influential Hall and Park families of North Bennington. Acting through a relative, he acquired the former site of the old Ethan Allen-Truman Squier house on the corner of Town Hill and Monument Avenue and turned the property into a private burial park for himself and family. He constructed a fairly large mausoleum around 1906, in the style of the time. There are two other mausoleums in the cemetery, although they are smaller and in less noticeable locations.

The Renascence

In 1907, about the time of the McCullough addition, the leaders of the renascence asked the Legislature for a cemetery charter. So the Legislature created the Bennington Centre Cemetery Association, a charitable organization, and gave it "charge and care" of the cemetery. The association was given the right to acquire land for cemetery purposes, but it did not receive title to the cemetery.

Led by McCullough, the association started improving the appearance of the cemetery. Mowing the grass was only a beginning, as there were sunken graves, broken trees, leaning and fallen stones, enough to take years to correct. Not only was there much work on the ground to be done, but there was the pressing problem of how to get the money to do the work. McCullough, aided by the Rev. Isaac Jennings, minister of the Old First Church, James C. Colgate, Samuel B. Hall, George Hawks, and others, decided to send out bills to lot owners, if known, and to offer memberships in the association to owners, if known, and to offer memberships to those who would work. These efforts brought in some money, but not enough.

One problem with collecting from lot owners was that the Town was the sole owner of the old part of the cemetery, since deeds had not been issued for any lots before about 1866. Although the Town owned all the alleyways, and still owned considerable lots in the "new burying-ground," the Town does not seem to have contributed. Another problem was that the owners of lots or their heirs were not always known, and even where the owners of lots were known, many would not pay. The association had no enforceable claim against them. It could hardly take care of some plots against payment and leave the remainder untended. The obvious solution was to create an endowment to replace the billing of lot owners for services. This effort has gone forward successfully to the present day.

After Governor McCullough's death and burial in his family mausoleum in 1915, his widow in 1921 donated the white wooden ornamental swag-fence across the entire front of the cemetery as seen today. In the 1920s, the McCullough executors and trustees decided to create ten burial lots in that portion of the McCullough plot, which had once been the site of the old courthouse.

The work of carrying on the association's duties and getting the daily work done on the ground from May to November passed to Frederic B. Jennings, James C. Colgate, Maude Galusha, and Dr. Vincent Ravi-Booth, minister of the Old First Church. These people served thirty years each, more or less, on the Board of Trustees and as officers.

The most recent enlargement of the cemetery, the "Southern Extension" took place in the mid-1930s. The idea of closing the lower part of Church Street and making it part of the cemetery was as old as the first unsuccessful association, but the proposal was given a push by the expansion of the Bennington Museum across the lower part of the road in 1927. It was not feasible to acquire the upper end of Church Street as well, because it served a small house on the Blackmer property as well as the Blackmer carriage barn, halfway along the street.

The Selectmen closed the lower part of the street, and Morton D. Hull, then owner of the Parson Dewey House and the land adjoining the street on the southerly side to the middle of the street, conveyed the south half of the street and some more land besides. The Selectmen conveyed the north half of the street. The association was then able to layout the parcel in twenty-five lots and offer them for sale, after filling up Church Street to ground level where it had been excavated in earlier years to make it less steep for travel. Where the street had once been, a stone and cement gutter was built to carry away surface water from the remaining street above, but as this gutter was not satisfactory, it was eventually replaced with an underground pipe.

Dr. Ravi-Booth worked for twenty-three or more years overseeing the day-to-day work in the cemetery. He found time in addition to lead the effort to increase the endowment. With his help it increased from $7,000 in 1919 to $22,000 in 1932. The Southern Extension added money to the endowment.

Another of Dr. Booth's special projects was to set up old, fallen, and crooked gravestones in cement. This work began in the late 1920s, and progressed a few stones a year as income permitted. The effort gathered speed in the 1930s as Colgate began to donate the money for the work, until it was finally completed. About 700 monuments were straightened, many of them set in a concrete foundation four feet deep reaching below the frost line. Dr. Booth was careful to point out that the definition of "perpetual care" did not include the straightening of stones or filling sunken graves. There is no doubt that before the project was finally complete, much work that might have been paid for by lot owners (if known) had been done at association expense to make the cemetery beautiful. Some who worked so long for the cemetery also helped increase the endowment by bequests under their wills. James C. Colgate left the association $15,000 on his death in 1944, and Frederic B. Jennings left a trust fund for care of his family plot to the Old First Church which pays the association. The latest large bequest came under the will of a long-time benefactress-trustee, Esther Dewey Merrill Parmalee. At this writing[1975], the endowment has reached $200,000 (in excess of $1.5 million as of 2019).

After World War II, Mr. Colgate and Dr. Booth were succeeded by Frank Lanagan, an engineer and surveyor who undertook two large projects in addition to his normal duties. He made a detailed map of the cemetery and put together a "Cemetery Record," which gives dates of birth and death and burial locations. The association adds to the list every year. In compiling the lists, the actual research was done by Ed S. Buss, who was for many years superintendent of the cemetery, aided by the Secretary Maude Galusha, and two local genealogists, Hazel Armstrong Wilson and Isabel L. Cole, all under the sponsorship of the Daughters of the American Revolution, with financial assistance in the earlier years of the effort from Mr. Colgate.

As of 2019 Vicky Printz has updated the list of interments and their locations using Lanagan's map. She has also made a separate list of all of the veterans interred who participated in the Revolutionary and other wars to the present. These lists are now available in the Old First Church and the Bennington Museum Library.

Despite the advice given over many years by Dr. Booth and Mr. Lanagan, the association had never seen its way to engage a full-time superintendent over the warm-weather work force who care for the cemetery. After Mr. Buss, the work was superintended by the same person, Alden Harbour, who cared for the Park Lawn Cemetery. When the double responsibility became too much for one man, Leon Cook became the superintendent. It appears that a full-time superintendent would be an absolute necessity were it not for the willingness of some members of the trustees to assist in supervision. Townsend Wellington, Weston Hadden, and Arthur Dewey were members of the executive committee, who donated time freely until their retirement. Charles Dewey followed his father by becoming a trustee. He has been the treasurer for over thirty years, and he has cleaned hundreds of the memorial stones, maintained the wooden fence, and added historical placards in the cemetery about notable people interred there.

Wynn Metcalfe, who worked for Leon Cook, became the superintendent after Mr. Cook retired. Since 2016 Jamie Jerome, great-grandson of Mr. Colgate, has been the superintendent, and he has made many improvements using the equipment from his construction company to correct deferred maintenance projects.

The burial in 1963 of the well-known poet Robert Frost has attracted more tourists to the cemetery than ever, and causes more visitors to walk through to view his grave in the Southern Extension. His wife, Eleanor, had predeceased him and her remains were brought here for re-burial. The records indicate that six relatives are now buried with the poet.

After one hundred and eighteen years of existence, the Bennington Centre Cemetery Association finds the cemetery and itself in an enviable state, the cemetery being in almost perfect appearance and the association being as blessed by an endowment as it could reasonably hope to be.

Conclusion

We might speculate on the emotions Samuel Robinson, senior, felt as he watched the burial of his friend, the widow Bridget Harwood, in that small, rough clearing of trees and rocks where the trails met, 264 years ago. What would he feel today if he could return from the grave in London to view mixed landscaped and peaceful acres of green trees and white monuments containing graves of his contemporaries, descendants, and others, dominated by a churh building, the kind he saw in London, which his community could never have afforded in his lifetime? We should think that Esquire Robinson would experience a certain sadness that his remains were not carried back from London to rest in this burying-ground.